Rwenzori National Park

The Legendary Mountains of the Moon

Introduction

21 January 2026 – 1 February 2026

“You may be familiar with the Alps and the Caucasus, the Himalayas and the Rockies, but if you have not explored Rwenzori, you still have something wonderful to see.”

Douglas Freshfield

The Rwenzori (Ruwenzori) Mountains are widely regarded as Ptolemy’s fabled Mountains of the Moon* which for centuries marked the edge of maps, often connecting to the entirely fictitious Mountains of Kong – that is an amusing story for another day – for both Arabs and Europeans, though neither had definitive reports of their existence. It would not be until the Victorian Era, when discovering the source of the Nile became a prize, that the legendary range would return to European attention.

When an 1856 Royal Geographic Society expedition to find a suspected Great African Equatorial Lake stalled at Lake Tanganyika, John Speke proceeded alone and became the first European to sight Lake Victoria. The controversial Scotsman, Samuel Baker’s, 1864 expedition met Speke and proceeded upriver from Lake Victoria to Lake Albert. From here, he made note of the ‘Blue Mountains’ in the distance. It wasn’t until 1888 that the existence of the mountains was fully confirmed when Henry Morton Stanley realised that what he had thought was cloud clinging to the slopes was actually glacier. Bad weather, dense vegetation, and short time continued to turn expeditions back until 1906 when the Duke of Abruzzi (best remembered for an unsuccessful 1909 attempt at K2 via the ridge that now bears his name: the Abruzzi Spur) was inspired by a quote in Stanley’s obituary and became the first to climb the six primary peaks of the range. He was accompanied by the premier alpine photographer of the era, and the photos are a window into a different time. Vast expanses of ice that seem wildly out of place in Equatorial Africa.

Enough colonialism though. The Bakonzo people have lived in the lower reaches of the range for centuries. They believed the mountains to be home to the god, Kitasamba. I have heard rather mixed things regarding how extensively they knew the inhospitable depths of the range – there is a significant lack of source material and all could be accused of dubious integrity. In the post-colonial era, Uganda has taken a very rational line on naming convention: the Victorian names are well established and changing them would only generate confusion. There are more than enough unnamed and even undiscovered locations that can be filled with local names**.

*The Duke of Abruzzi would claim this is a translation error and it should actually be ‘White Mountains’, a name that would match both the Arab name and have parallels to the more amusing Baganda name – ‘My Eye’s Pain’. Mountains of the Moon had already stuck though.

**Source – my [local] guides. Take it up with them if you disagree.

The extent of glacier coverage during a 1925 Rwenzori expedition under the flag of The Explorers Club

With an unexpected tax-rebate, I was in the market for an ‘unbudgeted’ holiday. Initially, I was looking at Bhutan or Tibet in April. But when a sunny-winter getaway to Kvaløya was pushed back to that month, I was forced into a rethink. January/February is the dry, or less wet, season in East Africa, so my attention shifted to a region I have long been interested in but always struggled to justify.

Kili is the obvious choice for an African mountain excursion. But with roughly 50,000 summit hopefuls a year, it has become quite the circus. Add in a stomach-churning bill, non-technical challenge, and offering little in the way of varied terrain or rugged views, I was not enthused. Uganda on the other hand…. solitude (Rwenzori NP gets roughly half the annual visitors of Gates of the Arctic NP, the least visited US national park), completely alien flora, and the continent’s only alpine climbing – now that is an adventure worthy of the trip!

I had heard nothing but positives from travel reports out of the country. But there were a few points making some cautious concern not at all unhealthy – particularly for the solo traveler unfamiliar with the region. The first is that all but the most nuanced of travel advice advises against travel within 50km of the DRC border (nuanced advice does exempt travel in national parks with reputable guides). I would be literally climbing that border and would even have the option of crossing (violating even more travel advice – though an alpine crossing is hardly in the spirit of that advice). Most critical though was the general election that was called for January. I had attempted to avoid it as much as possible but somehow ended up with the date-set closest. Given the current global electoral climate, elections are best avoided – anywhere in the world.

A guide is a requirement to visit the national park and there are only two operators. Each company builds, maintains, and has exclusive rights to their own route. I would be using the newer Kilembe Route, opened in 2009. Reviews for both the staff and infrastructure were distinctly higher, so it seemed the obvious choice. I intended to do their longest stock-itinerary: a 10-day circuit, taking in four of the highest peaks. Due to an irregular international flight schedule, I unfortunately needed to trim that to 9 days. I would lose one of the four peaks (Mount Speke), but I was still confident of a very successful programme.

Arrival

Wednesday, 21 January

The pre-departure drama began in November. A Yellow Fever vaccination is a requirement to visit Uganda and I seem to have had quite a nasty reaction to the shot. After a few days of the expected mild headaches, I was absolutely floored with the worst flu symptoms I have ever experienced, but only four a single day. I suppose that’s why we get vaccinated against such diseases…

Final preparations were then derailed by a four-day internet blackout for the election. It made for a stressful week, particularly as I still needed the arrival details to be confirmed from the trekking company. Fortunately, the ‘indefinite’ blackout was lifted at the earliest realistic moment: the evening that presidential results were announced (48hours after polls closed, as constitutionally stipulated). And now I know far more abut Ugandan politics than I ever wanted to know!

International flights were long, but surprisingly very straightforward. Amsterdam has one of only three direct (outbound landing in Kigali, Rwanda) flights from Europe to Entebbe so not only was booking direct a rare possibility, it was also by far the cheapest option! It was a very late arrival though, with the aircraft landing at 23:35. I did not reach my hotel until 00:50.

Yoweri Museveni welcomed me to Uganda: the Pearl of Africa. His face plastered on literally every surface of the airport. Say what you will about the man, but his PR team certainly knows what it is doing.

Kyanjuki Village (1500m) – Sine Hut (2596m)

Thursday, 22 January

All too quickly, I was back at Entebbe Airport for my 7:00 domestic flight to Kasese. A little more time to settle-in would have been nice, but it was my decision to not waste a day. I was already threading the needle with work-trainings, annual leave allotment, and an irregular international flight schedule. The early departure would also still have held if I had waited to head to the hills.

Against my better judgement, I took the hotel’s advice to leave for the airport at 6:00, with a 6:30 check-in deadline. It is important to note that this was just about the perfect timing. But it led to stress, which in turn led to me temporarily losing my wallet… never a good thing – all would be well though.

Self-imposed stress aside, the domestic flight was a delight. I was flying an airline that serves bushflights to Uganda’s national parks. There were three Cessna Grand Caravans parked on the apron and boarding passes were chunks of coloured plastic, with each colour being for a different destination. I was the last to board my full aircraft and ended up with the front, central seat with prime views of the instruments. My plane-mates were a group of Alabamans who operated a church in Kasese – pleasant people from a very different world…

The trekking company picked me up from Kasese Airstrip and we made the short drive out of town to Kyanjuki Village where the company headquarters is located. Kasese is quite a dry place, but things quickly turned green as we drove into the foothills. Leaving town, we followed the floodplain of the River Nyamwamba – currently very dry, but it regularly causes considerable damage and its path was littered with the ruined foundations of buildings.

Pre-departure formalities (insurance, mountaineering waivers, etc – standard stuff, but poignant given no SAR in Uganda) was followed by the pre-departure briefing and we were off! Kyanjuki Village made for an interesting start – the single dirt road flanked by vibrant shop stalls, endless political posters, and uniform, linear, rows of basic housing. It was a lively and sociable place, with everyone out and about. Uganda is a very young country, and that was certainly seemingly on display here as the road was thronged with waving children. I don’t like taking photos of people, even if indirectly, so unfortunately there is nothing to share.

The village is not large, and the road quicky came to an end as we started to traverse the hills above town, passing banana and coffee crops seemingly placed at random on the hillside and blending into the other vegetation.

Three-horned chameleon (male) hanging out next to park enterance

I would be spending the day in the afro-montane forest for the entirety of the day’s walking. A bit hot and sticky, but it was completely different walking for me. Instead of mountain vistas, the visuals were dense vegetation and the star attraction was the wildlife. There are illusive big-game animals (forest elephants, leopards, etc), but Rwenzori was heavily used for hunting until the national park was created in 1991 and chances of a sighting are extremely low. The leopards, in particular, were hunted nearly to extinction due to the local species having a particularly attractive coat. Instead, I was treated to blue monkeys and countless insects: line upon line of thousands of red warrior ants and dense swarms of multicoloured butterflies.

Forest views along the dry River Nyamwamba

A small rainstorm rolled through in mid-afternoon. Fortunately the dense vegetation blocked almost all of the rain and I did not need to break out the shell – it was sweaty enough in a wool t-shirt.

I had Sine camp to myself, something that would hold true for the majority of the trip. A Belgian couple started at the same time as I did, but they were doing just a two-day trek and therefore acclimatisation was of little importance. They continued to an intermediary camp. Fortunately, at 2600m, temperatures had fallen sufficiently to be considered more a pleasant summer evening, if a bit humid.

A thunderstorm rolled through over dinner.

Sine Hut (2596m) – Mutinda Camp (3688m)

Friday, 23 January

Almost immediately upon leaving Sine Camp, I entered the bamboo-mimulopsis zone. The dense tress thinned and were replaced by bamboo and strange flowers, along with increasing views of the surrounding hillsides. This was to be short-lived though as we quickly moved into the heather zone, probably the most varied of the zones. In this part of the zone, I had low plants and a sporadic sprinkling of giant heather trees. On a good day, I would have had views out of the mountains into Queen Elizabeth National Park. Instead, a dense haze covered the lower hills and valleys. It was not a morning for photography.

Shortly after entering the heather zone, we reached Kalalama Camp – the intermediary camp the Belgians had stayed at. And what a camp it was! Sine was pleasant, I particularly enjoyed the dining patio, but this was on another level. It still had a forest feeling, but because of the higher vegetation zone, it offered far better vistas. Looking down from the dining patio was Queen Elizabeth NP. In the other direction were giant heather trees dripping with usnea lichen and distant rocky outcrops.

Giant heather trees outside Kalalama Camp

About an hour beyond Kalalama Camp we arrived at the base of a moss covered stream and the first of many completely otherworldly locations. A steep section of stream banked by moss covered tress and 4000m rock pillars. Pushing up the stream/waterfall we were then greeted by the first lobelia garden – tall spikey flowering plants that grow in boggy parts of the heather zone.

The relentless upward push continued, now interspersed with an increasing number of boardwalked sections and rickety ladders. The ground was largely dry for me, but I got a good warning when I stepped on a small innocent looking dark patch of ground and watched my leg disappear into mud.

Shortly after arriving at camp, dense cloud began rolling up the valley. Mutinda lookout towers above camp, and an ascent is listed in the programme as an afternoon option (also the primary objective of some shorter itineraries). Going into the day, I was very keen to hopefully see the views from the top, but apprehensive over potential damage to acclimatization. I felt good, but my experience in Nepal indicated that I should be extremely careful about over-doing things and that ‘climb-high, sleep-low’ is far less crucial. Mutinda Camp was a big jump over Sine Camp and the next 36 hours would be critical in determining whether I would manage to acclimatize properly.

My guides made no mention of the option and I hesitated to bring it up due to the combination of acclimatisaion concerns and heavy cloud. The afternoon slipped by as I debated but by mid-afternoon the cloud appeared to be lifting and I figured I may as well ask. By that point I was told that it was too late though. Instead, I went for a wander myself. I started by taking the lookout bootpath myself. It was steep, wet, and very heavily vegetated. Not a straightforward undertaking, even for a very experienced hiker. Before too long I reached a point that I decided I should not progress beyond on my own – the bootpath completely disappeared into the vegetation and I figured there would be awkward questions if I got myself into trouble… I had some excellent views of the surrounding hills, though I didn’t manage to find the overhead view of camp I was after.

Mutinda Camp

After descending, I made a preview of the next day’s route. A remarkable area and the intermittent cloud only added to the visual. Mutinda Camp just feels like it does not belong on this planet. A young Eric Shipton (1951 Everest reconnaissance expedition leader, controversially deposed for the successful 1953 climbing expedition) summarized the feelings of the area more eloquently than I

“it felt as though we had emerged from a world of fantasy, where nothing was real but only a wild and lovely flight of imagination. I think perhaps the range is unique. It is well-named Mountains of the Moon.”

Eric Shipton, 1932

First kilometer from the next day’s plan, outside Mutinda Camp

Come evening, I was very happy to have my layers and jackets – the day had been warm, but evening temperatures were now significantly cooler.

Mutinda Camp (3688m) – Bugata Camp (4062m)

Saturday, 24 January

It was a short day to Bugata Camp – 6.5km and 500 vertical meters. In that distance, I would be transitioning from the heather zone to the afro-alpine zone.

We started the day on the boardwalked section I had explored alone the previous evening. Before long, the vegetation disappeared, with only skeletal looking trees covered in lichen. Apparently, there was a bushfire back in 2012 and the area is still recovering.

Entering the burn-zone

This was a day of extensive boardwalks. Fortunately, they were not necessary in the conditions I encountered. It was obvious how boggy it could get in wetter conditions though, and I would get a small taste of that a few days later when traversing the same zone on my way out.

After a short climb, we reached the broad Namusangi Valley and the afro-alpine zone. The landscape opened significantly, with boggy grassland.

We reached camp at noon. A pleasant spot, perched on a rocky outcrop overlooking a glacial lake and across from the extremely broad and many-summitted Mount Luigi di Savoia. Back in Abruzzi’s day, the glaciers extended this far down the mountain.

Cloud once again rolled in shortly after lunch. I had intended to go out for a stroll mid-afternoon but was stopped by rain. It was neither intense nor long-lived, but I had nowhere I needed to be.

Views from Bugata Camp

Bugata Camp (4062m) – Hunwick’s Camp (3974m)

Sunday, 25 January

Today I would be heading to Bamwanjarra Pass (4450m), where I would get my first views of the main peaks, before descending to Hunwick’s Camp. The pass is named for a local figure who was central to the Victorian exploration of the range. He was head porter for Abruzzi and took part in nearly every expedition until 1940 at which point he would have likely been 70 (he was unsure of his exact age).

It was quite a windy night and had been clear until sunrise. By the time I was headed to breakfast, cloud was beginning gather. Nothing particularly threatening, but a clear break from the pattern of the previous days.

The ascent to the pass began through similar terrain as the second half of the previous day – broad rolling hills in the slightly singed afro-alpine zone. After about an hour, the ascent quickened and the vegetation grew denser again.

Changing vegitation on the way to the pass

Reaching the pass, I was treated to my first view of the main massifs: Stanley, Speke, and Baker. To the west, the ceiling was dropping, but still just above Margherita Peak. To the east, back toward Bugata Camp, skies remained clear. The views in either direction were starkly different.

It was an extremely steep descent through lush vegetation. Like the area surrounding Mutinda Camp, this stretch just doesn’t seem like it should exist on this planet and such a difference from the other side of the pass.

Bamwanjarra Pass – My first view of the main peaks

On the way down, we ran into some gentlemen from the other Rwenzori company. Apparently they are interested in connecting routes and were doing some scouting. It would be great for both companies if it were possible to share routes, but there are some complexities to resolve.

Boggy below the pass

After traversing the boggy base of the valley next to a trio of glacial lakes, I was faced with a 200m descent before a 200m re-ascent into camp. On the map, the descent looked near-vertical. Topographic lines and trail locations are not necessarily to be believed in Rwenzori and elevation profiles can be deceiving at the best of times – these were not the case here. It was an extremely gnarly path. Fortunately, it was equally interesting, with lush exotic plants and views into both the narrow valley between Stanley and Baker and down into DRC. I was very glad the ground was dry though. It would have been a nightmare in the rain.

Looking down into Virunga National Park (DRC)

Looking up at Mount Baker before climbing back up to Hunwick’s Camp

Fortunately, the re-ascent was rather more kind and before long we were in camp. It was a surprisingly draining day, but after a fifteen minute nap and snack, I was well recovered.

Layering was a real challenge all day. In the sun it was a warm summer day. In the shade, it was chilly, and the sporadic wind only compounded things further. I also definitely have not yet figured out where the new sunshirt fits into the layering system.

Before dinner, a thunderstorm rolled through.

Mount Baker, Edward Peak (4843m)

Monday, 26 January

The objective of the day was Mount Baker, the sixth highest mountain in Africa. The eight-day version of my trip would have Baker as an optional (and unlikely) objective rolled into the day heading for high camp. With nine days, I was able to plan for the mountain to have its own day, allowing for more comfort and acclimatisation time. I would descend back to Hunwick’s camp and progress the following day.

1906 was a busy year for the mountain, with both Austrian and British expeditions being turned back before Abruzzi finally succeeded in June. Franz Stuhlmann had named it Semper during his 1864 reconnaissance, in keeping with his theme of German philosophers. Abruzzi changed the name to honour Samuel Baker (as opposed to Washington’s Mount Baker, which is named for Joseph Baker) and that name has stuck. The true summit was named for the British king by the Duke.

A 5:00 departure was set, so a 3:30 wake-up and 4:00 breakfast. The estimated summit time was 8:30.

There isn’t much to report from the early stages of the climb. It was dark, afterall. But when we stopped for a break at Freshfield Pass, I was able to see the lights from Mutwanga, far below in DRC.

At just about exactly sunrise, we reached a rock outcrop marking the ‘real’ start of the climb and had excellent views of the main objective: Mount Stanley’s Margherita Peak. Uganda does not seem to really get sunrises – the sun just kind of suddenly appears.

Sunrise as we attain the upper ridge

The main objective: Mount Stanley

The ridge scramble that comprised the main climb was thoroughly enjoyable. With conditions dry, we only used a single pitch of fixed rope, set above the pathetic remains of Baker’s last glacier. Even five years ago, an impressive volume of ice remained here. Now there is a pitiful patch, barely a few square meters in size – not even qualifying as a snowfield. I had actually been told to pack the crampons, not for ice, but for the potential of wet moss. Never heard that one before!

We summitted at exactly 8:30. Perfect timing too, as heavy cloud was rapidly closing in from the north. After some photos and a snack, it was back down.

Freshfield Pass

Because we had returned so early and things had gone so smoothly, my guides pitched the option of heading for high camp that afternoon instead of the next day. It would be roughly a three hour walk, with non-trivial elevation gain (numbers impossible due to obviously incorrect topographic data). This would move the summit attempt forward, but either introduce the potential for a second attempt in case of weather or make for a more relaxed descent out of the mountains. It would also make more room at Hunwick’s Camp, where there was a couple on their way up behind me and a couple on the way down ahead of me. On the other hand, it would run the risk of altitude issues due to overexertion.

I chose to take the accelerated programme. I was tired after the morning’s climb, but I do like my independence. As soon as we left camp, the rain began. The initial stretches followed a narrow valley along two glacial lakes. If visibility had been good, it would have been a superb walk, instead it was a bit of a slog through the rain and mud.

As we started to ascend Scott-Elliot Pass, it continuously teased a cloud-break. Each time, more would roll in as soon as I was sure it would finally happen. Gaining altitude, the trail changed from thick mud to slick boulders – not necessarily an improvement, particularly when physically and mentally fatigued.

Looking down Scott-Elliot Pass to Bujuku Hut, I was very glad to not be doing Mount Speke and the 10 day programme. That plan had always looked ambitious and it was a very long way down to the hut before an equally long way back up Speke.

From the pass, I still had 220 vertical meters to high camp and I was regretting my choice to push on. A quick nap at camp helped considerably, but I was still apprehensive regarding energy levels for the big climb – it isn’t like I would be getting much sleep that night. My blood-oxygen levels, which had been stable in the low-90s/upper-80s, made a noticeable drop.

Unfortunately, the mist only seemed to settle over dinner.

Mount Stanley, Margherita Peak (5109m)

Tuesday, 27 January

Summit Day 2: learning to live with your dubious decisions of the previous afternoon

Mount Stanley is a complex massif, with a jumble of spires instead of a classic summit. It has three peaks over 5000m and six more peaks over 4900m. The two most prominent are Margherita and Alexandra – named by the Duke for the Italian and British queens. My target was the true summit, Margherita Peak. Despite Stanley being Africa’s third highest mountain, neither Bass nor Messner include Margherita on their Seven Third Summit lists (Kili’s second peak, Mawenzi, is listed instead). Climbing grade is basic – generally reported as PD+. The rapidly melting glaciers mean that things are ever changing though and as the glacier disappears, the route has become more technical.

A 2:00 start meant a 00:30 wake-up and 1:00 breakfast. If conditions were good, we could expect a 5-7 hour summit push followed by a 3-4hour descent. If conditions didn’t cooperate, all bets are off…

Unsurprisingly, I was still tired after the previous day’s efforts. It was clear that I would be suffering on this climb and the less that is said about blood-oxygen levels the better… We started just five minutes behind schedule under a star-filled sky.

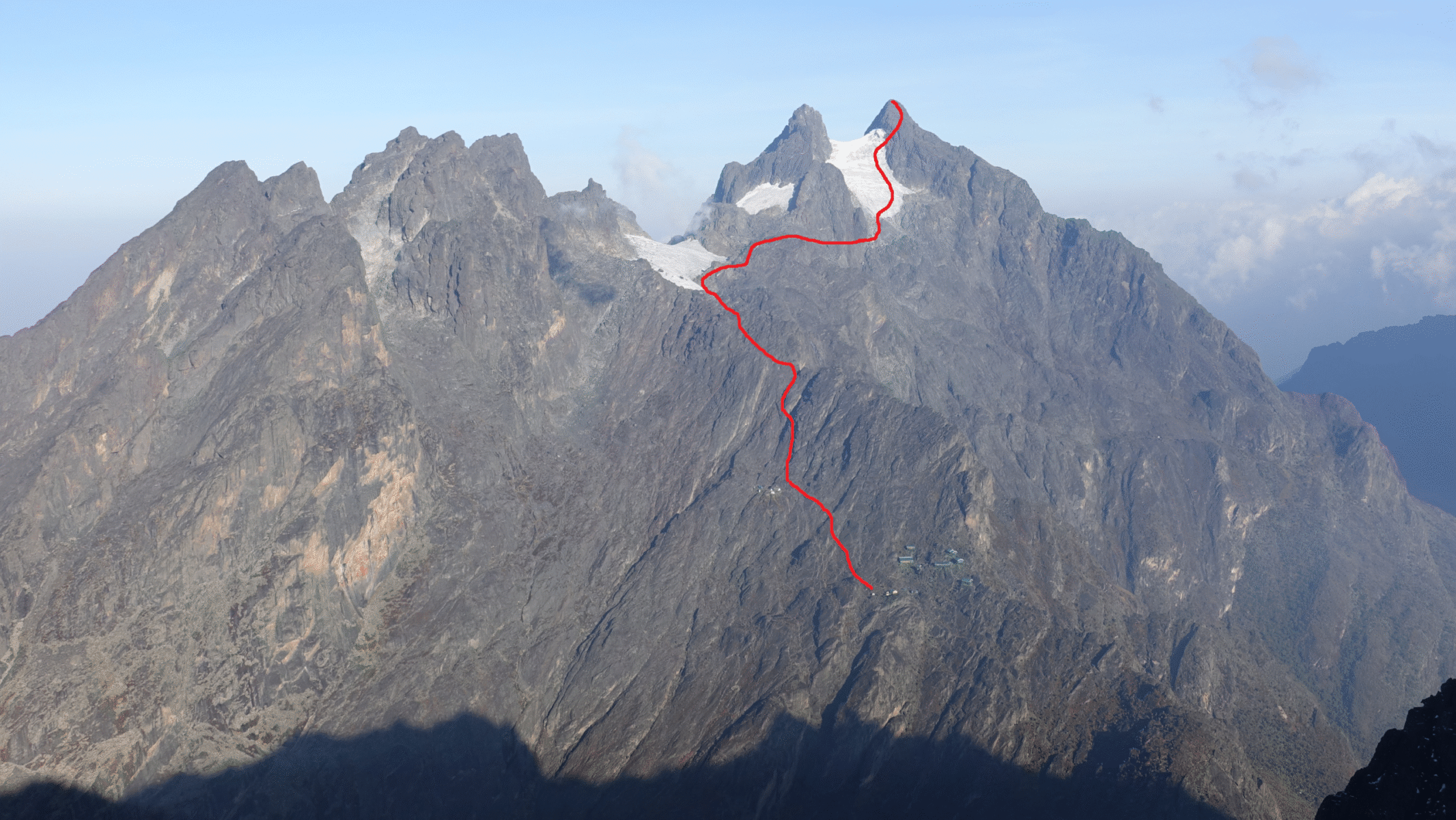

My attempt at drawing the route, as seen from Mount Baker. The old route spent considerably more time on a considerably larger lower glacier.

Initial stretches were characterized by straightforward scrambling but we soon reached the first fixed rope – two pitches of jumar work. Turns out, it is far easier to operate a jumar when the ropes aren’t covered in ice. Shortly after I was ascending fixed lines, I was abseiling down others. I was not aware of just how much down was involved in climbing Margherita. Of course any down-climbing just meant I would need to reascend that same distance.

At the top of that first line, I could hear the torrential rush of meltwater off the glacier – a sound that would persist throughout the climb.

The next landmark was an extremely brief and non-technical outing on Stanley Glacier. We did not rope-up or even get the crampons out. Apparently this is a new route, previously the lower glacier was used as a highway to avoid additional technical pitches on rock. Sadly, the glacier has melted sufficiently in the last few months that this is no longer viable.

The pattern of scrambling punctuated by ascending or descending fixed lines continued until we reached the base of Margherita Glacier. Here we did rope-up and put on crampons for an enjoyable glacier romp up the 55degree slope. The glacier terminated with a very steep traverse next to the randkluft. One of the companies bolted a metal walkway to the headwall at one point, but this was extremely decrepit and now an obstacle further narrowing the traverse to a knife-edge. After this, we de-cramponed, leaving them on the mountainside before making the final ascent of the summit block.

We topped out at 6:45 – exactly on schedule and roughly 15 minutes before sunrise. Throughout the ascent there had been frequent flashes, bright enough to momentarily fully illuminate the sky – likely lightning. Through those flashes, I had seen heavy billowing cloud rapidly closing in and unfortunately it had enveloped us as we de-cramponed. I shared the summit with a German woman who summited moments behind me and was the only other group on the mountain (she was two, but her partner and second guide abandoned the climb after the first jumar). We spent a cold thirty minutes on the summit waiting for the sunrise and hoping for a cloud-break.

The briefest of cloud breaks

Albert Peak was tantalizingly close. It would have been possible to climb this too (for an extra cost – fair enough, fully within the borders of DRC, a different country). Sadly it just didn’t make sense. Not only was the weather far from brilliant by sunrise, but I had definitely knocked my acclimatization back and it was still a long way down.

I struggled on the descent. My breathing was perpetually heavy and heart rate very rapid. There was no indication of serious AMS (or worse), though brain-fog and fatigue were increasingly settling in. When putting crampons back on, I twice failed to recognize that I was trying to put the wrong crampon on the wrong foot (it actually did register when first looking at them, but I must have incorrectly swapped them when actually going to put them on)…

With the ascent entirely done in the dark and the descent done entirely through cloud, I never had the opportunity to properly orientate myself on the mountain.

Mount Luigi di Savoia, Weismann’s Peak (4620m)

Wednesday, 28 January

Overnight there was a significant storm. Around midnight there was heavy rain and wind sufficient to physically shake my cabin. I was feeling very glad that I already had Margherita in the bag – a whiteout summit is always better than no summit. The French guy was due to start up at 2:30. I had heard him depart, but all his technical gear was sitting on the table when I arrived for breakfast. Apparently he had turned around at the first jumar.

I was now off-script. The new plan for the day was to descend back to Hunwick’s camp before returning to Bugata Camp via Weismann’s Peak instead of Bamwanjarra Pass. Weismann’s Peak is the second highest point on Mount Luigi di Savoia. Despite bearing his name, Mount Luigi di Savoia is the only mountain in the range NOT climbed by the Duke. The true summit, Stella Peak is 500m away and 6m higher, but involves a technical rock traverse for minimal payoff. Stella Peak was not offered as an option, but I can assure you that a technical pitch on mud and very wet rock in gumboots would absolutely not have been an appealing prospect regardless.

It was a beautiful morning, but heavy cloud was clearly gathering. Due to the previous evening’s weather, I would be wearing gumboots all day. I was not at all comfortable in them, particularly on the wet rock. But they were essential for dealing with the endless quantities of mud.

Views from Scott-Elliot Pass – before the cloud rolled in

The cloud had rapidly thickened as we descended. We reached Hunwick’s Camp at 10:30 where we stopped for lunch. Just in time for the rain to begin! Unlike other days, this rain had that ‘settled’ feeling and would not relent until evening. At least we were stationary and with a roof when it started – it makes a big difference when you can comfortably adjust layers whilst dry.

On the way to Weismann’s Peak, looking back where I started the day during a cloud break. Central is Scott-Elliot Pass, flanked by Stanley (L) and Baker (R), and both Hunwick’s Camp (RTS) and Kitandara Hut (RMS) in the valley.

As we ascended, I was still definitely not at 100% aerobically and the climb was both physically and mentally draining. Weismann’s ‘Peak’ is little more than a light scramble, but with the extremely slick rock and unfamiliar footwear, it required constant attention. The rain turned to hail around 4100m and wet snow was gathering above about 4300m. I am quite sure there would have been great views, but I was firmly in the cloud.

I had an enjoyable evening talking with a Swiss gentleman on his way up. Though because I arrived later, I ended up with quite the claustrophobic bunkhouse – to myself – instead of the luxurious double bed I had the previous stay in Bugata.

It was good to have one day deliver the ‘true’ Rwenzori experience, I suppose. I am glad it was just one day though.

Bugata Camp (4062m) – Forest View Camp (2600m)

Tuesday, 29 January

I woke to a surprise, a real sunrise! Likely caused by the uncertain, but slightly sinister, cloud clinging to Mount Luigi di Savoia.

The day’s objective was descending to Forest View Camp. Had I stuck to the programme, I would be hiking from Hunwick’s Camp to Kikaro Camp via Wiesmann’s Peak. It certainly would have been a more pleasant day for Weismann, but that was not known at the time and the alteration meant both a more relaxed exit from the hills and the opportunity to see a more varied route on the area’s newest trail.

It was a chilly morning, and I was both looking forward to not always being cold, but also trying to savor the cooler temperatures given the steamy climate I knew lay in wait. Deciding on a layering system for the day was going to be a challenge.

The morning started retracing the upper reaches of Namusangi Valley. This was old ground, but it was good to be descending to thicker air. Eventually, we split off for the Nyamwamba Valley. This track is absolutely not for the feint of heart, it is a prolonged plunge into the valley and was largely comprised of thick mud. The 1937 McConnell expedition tried and failed to find a way up this valley and apparently it took six years for the company to find a suitable path for trekkers. The scenery was absolutely worth the effort though!

Namusangi Valley

After the rapid and muddy descent, we arrived at Kikaro Camp at about 11:30. What a location! I was a little sad not to be staying. The cloud that had been threatening all morning began to gather, but still no rain. Temperatures had warmed significantly, but were still quite pleasant.

A short stop later and we continued down the heather zone as vegetation increased in density. Sometime shortly after Kikaro, we split off onto a spur trail that would connect to the ‘waterfall circuit’, the region’s newest trail. I’m not really a waterfall person, but the three falls were quite pleasant. Apparently these were only discovered in 2020 – that goes some way to show just how unexplored this area is and an indication of just how wild the range is to this day.

Area around Kikaro Camp

After the waterfalls, we descended back into the bamboo zone. Temperatures were soaring and the increased vegetation meant vistas were increasingly limited. But the chances to spot wildlife were also increasing and there were more than a few blue monkeys about. Apparently they regularly need to re-rout this section due to landslides. Given how steep the slopes are, I can’t say I am surprised.

Back to the forest

Forest View Camp is certainly aptly named and I had exceptional views down the Afro-Montane Forest from the dining area. Two ridgelines down, I could see civilization in the form of Kyanjuki’s hill-farms.

Much to my surprise, this was one of my favourite days! The variety was unparalleled as we traversed most Rwenzori’s stupendous wealth of vegetation zones.

Forest View Camp (2600m) – Kasese (910m)

Friday, 30 January

It was a warm and not the most comfortable night back down at modest altitude. We were still at 2600m, but temperatures were on par with a hot summer night. My sleeping system is just not set up for that. The real problem was brining back the mosquito netting though – quite the cumbersome system that exponentially compounded discomfort.

Because of the schedule change, it would be a short walk-out with only 5.6km and 925m of descent to the park gate and another 3.3km and 311m back to headquarters in Kyanjuki Village. It may have been short, but temperatures soared making it a sweaty walk.

One of my final views of Rwenzori, from the hills above Kyanjuki Village

A short drive out of the foothills and into the much drier Kasese town and I was checking in for my final night in Uganda. I had been looking forward to a shower and being clean(ish) again. Of course the power was out when I arrived – hardly abnormal and I was prepared for it. Still, not what I was hoping for – no internet, no air conditioning, but at least I could shower. It took a little longer than expected, but power was restored.

When planning, I had thought that it would be a pleasantly relaxing stay. In reality I was stressing about the homeward journey’s travel arrangements.

Departure

Saturday, 31 January – Sunday, 1 February

The plan for the homeward journey had been to take a morning bushflight back to Entebbe, where I would have most of the day to relax. Bushflights are subject to scheduling alterations due to capacity, with the final routing confirmation given 24hours before departure. The Kasese-Entebbe route also requires a minimum of two passengers. Given that I was solo, I was particularly vulnerable to alterations. My mid-morning flight was moved to be late-afternoon to align with other passengers and I would be routed via Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. A totally justifiable alteration, but it meant that my relaxing final day became considerably more nervy – in the last year I have had more flights with issues, including serious issues, than smooth – often for seemingly inexplicable reasons.

The flight change actually opened the possibility of a visit to Queen Elizabeth National Park for a game-drive and/or river cruise – options that my driver into Kasese was keen to [politely] push. It was a tempting option, but one that I was never going to take. I was already stressed over the homeward journey. Throwing in a last-minute logistical complication would have only compounded that stress and been far from enjoyable. Additionally, a commercialised half-day game-drive just didn’t seem like something that would do justice to the animals/region. Instead I rotted away at the hotel and enjoyed the desperately needed air conditioning after ten days in the backcountry.

My private ride out of the hills

Forty minutes prior to scheduled departure time, I made the five minute drive to the airstrip. As my passport details were being manually recorded in the logbook, the aircraft landed. I loaded my bag into the cargo-hold and we took off ahead of schedule. This time, my plane-mates were a small group on their way to see the gorillas in Bwindi. Before taking me to Entebbe, they would be dropped off at Savannah Airstrip. This routing was actually a blessing as it meant I got to see a great deal of Uganda from the low cruising altitude of a Grand Caravan. We were much too high to pick out animals, but plenty low to get a detailed overview of the landscape as we overflew Katwe Craters and Queen Elizabeth National Park.

After a five minute stop on the ground, I was back in the air for the hour leg back to Entebbe. A thunderstorm was rolling over Lake Victoria as I flew the rather more complex Entebbe approach procedure leading to a bit of a bumpy descent before my tiny aircraft landed on the comically oversized runway (777s need a bit more runout than a Grand Caravan).

At this point I was in for a absurdly short stay back at the Entebbe hotel. This was not the intent – I was supposed to have had most of the day. Instead I had about three hours – just enough time for a shower, nap, and final repacking. Better than hanging out at the airport though and it was pre-booked. It was also cheaper than almost any airport charges for even a sleeping pod or lounge (Entebbe Airport has no on-site options).

As I passed the outer bag-scan at the airport, who do I run into but the Belgian couple who started their two-day trek at the same time as I was off for my nine-day.

A long overnight flight later, and I was almost home. Unfortunately, my positive feeling was brought crashing down by a particularly nasty interaction with Dutch border control. It has been an increasing problem at Schiphol, but this was really beyond unacceptable. It was still bothering me several days later.

Afterwards

I have wanted to do something in Africa for some time now, and I can now say that my curiosity has been satisfied. Rwenzori was my top pick on the continent and I am glad I held out for it. It was a completely otherworldly experience, and one that will not be possible for much longer.

A few notes on practicalities:

- This was a very condensed programme. I knew what I was getting into going in and my only concern was acclimatisation. I had the impression the guides were not thrilled with how condensed the company’s offerings were – a lot of disappointed clients.

- I have heard veterans of the Snowman Trek (Bhutan, widely regarded as one of the world’s most difficult multi-day hikes) claim that the 8-day Margherita Peak itinerary is more punishing. I can’t comment on that but whilst no single aspect in Rwenzori is particularly challenging, put all the variables together and the picture changes.

- There are literally no paper maps of Rwenzori. None at all. Digital maps are passable, but the topographic data is often obviously incorrect, particularly surrounding the main peaks.

- Rumour has it, the companies are considering installing what would be the highest via ferrata in the world once the glacier has melted. I very strongly disapprove of such destructive ideas.

- The trekking style was quite extravagant, particularly for this perpetually solo ultralight hiker. Two guides and ten(!) porters joined me (note – I would hike with just my two guides). I certainly never wanted for food/drink and there was an assortment of unnecessary luxuries. I may not have been able to compete with the Duke’s half-kilometer porter-caravan, but it was a style very unnatural to me.

And assorted personal takeaways:

- With glaciers having retreated by 29.5% between 2020 and 2024, I cannot stress how happy I am that I was able to make this trip happen. It will not be long at all before they are gone forever. I doubt they will survive to see the end of the decade. In 2006, it was predicted the ice (ice, and not glacier) would be gone by 2025 – fortunately, it is still clinging on, but only just. I don’t see them lasting more than another year or two.

- I will continue to question whether I should have added a safari (gorilla, chimpanzee, or savannah all possible). It is always possible to add more to a trip, but it is important to keep perspective on what my priorities are rather than chasing someone else’s bucket list. Budgets are finite – both financial and annual leave and I want to sure to spend mine in the way that best suits me.

- I may have still encountered minor altitude issues, but this was a massive confidence boost for future endevours. I successfully completed an accelerated version of an already quite aggressive programme with rapid acclimatisation.

- I really did feel like a Victorian explorer – both for positive (venturing into the uncharted, unknown, and alien) and negative (legacy of colonialism) reasons.

- I am the very last person to gush about ‘the people’ in a travel destination. But interactions were almost universally positive here – people were just genuinely helpful and kind, and without feeling transactional (as in Nepal). The cultural whiplash landing back in NL was difficult to take.

- It was definitely a plunge to make my first trip to Africa, and solo. It is easy to make bookings but eventually those bookings become an imminent reality. Ultimately, everything went as smoothly as could possibly be expected.

- As much as I enjoyed this trip, I do not think I am in a rush to return to Africa. The climate is not for me, the general travel style required is not for me, and whilst there are many very interesting places, nowhere else has the personal appeal to pull me away from other big-ticket destinations. Madagascar is likely the exception, but I do not even know where to begin there.

Photography was perpetually frustrating as I was continuously challenged by difficult lighting and atmospheric effects. My efforts can’t come close to capturing the wonder of some of these areas. Though in many ways, it is simply the kind of place that must be experienced to comprehend.

Footnote

All photos are exclusive property and may not be copied, downloaded, reproduced, manipulated or used in any way without permission of the photographer.

Leave a Reply